Week 3

2024-09-17

1 Preparing data and accessing RStudio Server

Please start by logging into rstudio.pomona.edu.

1.1 Load packages

Below, we will start by loading packages that we’ll need. Remember,

you may need to run install.packages('PACKAGENAME') just

once this semester if you get an error for a particular package.

### Load packages

library("ggplot2") # plotting functions

library("dplyr") # data wrangling functions

library("tidyr") # data wrangling functions

library("readr") # reading in tables, including ones online

library("lubridate") # a package to specify date-time stamps

library("mosaic") # shuffle (permute) our data1.2 Read data

Next, we will pull in our data.

### Load in dataset

temperature_data <- readr::read_csv("https://github.com/EA30POM/site/raw/main/data/temperature-c.csv")

pm25_data <- readr::read_csv("https://github.com/EA30POM/site/raw/main/data/us-epa-pm25-aqi_claremont.csv")

### How many observations and columns do we have?

dim(temperature_data)1.2.1 Using the

View command

Oftentimes, we may want a more intuitive way to see our data tables.

It can be really annoying when R is too clever and only

displays a subset of the columns of your spreadsheet. The

View() function pulls up an Excel-style data viewer. Let’s

try it below:

View( head( temperature_data ) )1.3 Cleaning the data

Below, we are going to modify some of the data attributes to be able to seamlessly join these two variables together.

# Clean the DateTime column using lubridate's ymd_hms function

temperature_data <- temperature_data %>%

mutate(DateTime = lubridate::ymd_hms(DateTime))

pm25_data <- pm25_data %>%

mutate(DateTime = lubridate::ymd_hms(DateTime))Now, we are going to cast these data to a “long” format (each row is an individual observation only) so that we can more easily match across datasets.

# Convert the temperature_data to a long format

temperature_long <- temperature_data %>%

tidyr::pivot_longer(cols = -DateTime, names_to = "Station", values_to = "Temperature") %>%

dplyr::distinct(DateTime, Station, .keep_all = TRUE)

# Convert the pm25_data to a long format

pm25_long <- pm25_data %>%

tidyr::pivot_longer(cols = -DateTime, names_to = "Station", values_to = "PM2_5") %>%

dplyr::distinct(DateTime, Station, .keep_all = TRUE)Now we are ready to join our data! We are going to join based on

matching values for Station and DateTime.

# Merge the temperature and pm25 data by DateTime and Station

airDF <- inner_join(temperature_long, pm25_long, by = c("DateTime", "Station"))

# Create separate columns for Date and Time

airDF <- airDF %>%

mutate(

Date = as.Date(DateTime), # Extract the date

Time = format(DateTime, "%H:%M:%S") # Extract the time in HH:MM:SS format

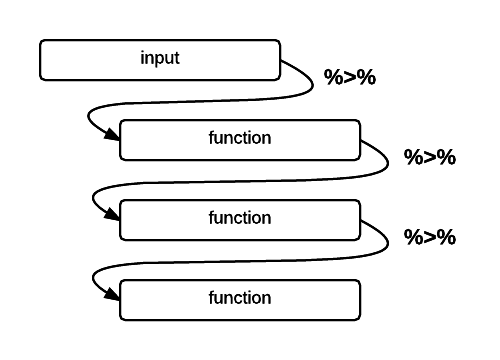

)I’m going to use the pipe operator %>% to daisy chain

commands together into a sequence. It is a handy way to make a complex

operation with intermediate steps more transparent. The visualization

below describes what pipes do in R in linking up

functions:

%>%

operator in R (Altaf Ali)airDF %>% head() %>% View()1.3.1 Pre-processing the data

Now we’ll use that handy %>% operator to clean our

data. We’ll also use a very helpful function called mutate.

mutate is a command to either alter an existing column or

create a new column in the data.

### Pre-processing steps

# We want the Date and Time columns to be datetime objects

airDF <- airDF %>%

mutate(Date = lubridate::ymd(Date), Time=lubridate::hms(Time))

# We want to code which observations are made in the day vs. night

# using 6pm as our cut-off

pm_limit <- lubridate::hms("18:00:00")

### Add on a new column to note whether or not the data is day or night

airDF <- airDF %>%

mutate(DayNight = case_when( Time >= pm_limit ~ "Night",

TRUE ~ "Day"))

### Remove rows with missing values

airDF <- tidyr::drop_na(airDF)2 Analyzing the data

Below, I provide fully-worked examples of different ways of

inspecting your data and performing analyses assuming that

PM2_5 is the variable of interest. In applying

this code to your own data, you will want to think about what variable

name should replace PM2_5 in the commands

below.

Let’s start with exploratory data analysis where you calculate

summary statistics and visualize your variable. Let’s say that I’m

interested in understanding how the values of PM2.5 (PM2_5)

vary across day and night (a silly example, I know). We’ll use another

function: group_by splits a data table into groups based on

distinct values a variable that has categories. In this

case, we tell group_by to divide up the airDF

data table into groups based on the values of DayNight. We

then will use a function summarize to get summary

statistics of PM2_5 in the day and night.

### Calculate summary statistics for PM2_5

### for each DayNight condition

airDF %>%

group_by(DayNight) %>%

summarize(min=min(PM2_5,na.rm=T), mean=mean(PM2_5,na.rm=T), max=max(PM2_5,na.rm=T))

# use DayNight as the grouping variable

# for PM2_5 and then summarize PM2_5

# for each value of DayNight and pass in the parameter

# na.rm=T to ignore missing values2.1 Do day and night differ in their PM2.5 levels?

How do PM2.5 levels vary across day and night? We can visualize that using a boxplot. Boxplots are useful for depicting how different discrete categories within a variable exhibit variation. Below, we will specify the variable that we use to group our data (Day/Night) as the x variable, and the values of interest as the y variable (PM2_5, or PM2.5).

p <- ggplot(airDF, aes(x=DayNight, y=PM2_5))

p <- p + geom_boxplot()

p <- p + labs(x="",y="PM2.5 (PM2_5)")

p <- p + theme_minimal()

pLet’s calculate the difference between Day and Night in terms of

their mean PM2_5 values.

### Calculating differences in mean PM2_5 values

obs_diff <- diff( mean( PM2_5 ~ DayNight, data=airDF, na.rm=T ) )

obs_diff # print out the valueOK, so we see that there is a difference in mean PM2.5 levels across day and night. Is this a meaningful difference though? Our null hypothesis is that there is no difference in mean PM2.5 levels between day and night (again, a silly example, I know).

Logically, if there is a meaningful difference, then if we shuffle our data around, that should lead to different results than what we see. That is one way to simulate statistics to test the null hypothesis. And specifically, in this case, we would expect to see our observed difference is much larger than most of the simulated values.

What does simulating our data look like?

Well, here is what the data look like initially. We’re going to use

another function, select, to pull out particular columns of

interest from the data.

airDF %>%

dplyr::select(Date,Time,PM2_5,DayNight)Here’s what the data look like if we shuffle it by randomizing the

assignment of observations as day or night. This is like a chaos agent

coming around and slapping a new label for day or night on at random for

every row in the data table. (But if we think mean(PM2_5)

is the same for Day and Night, then that

should be a perfectly OK action by the chaos agent.)

print(resample(airDF[,c("Date","Time","PM2_5","DayNight")],groups=DayNight,shuffled=c("PM2_5")))We can repeat that procedure again and see how the data shifts if we do another shuffle.

print(resample(airDF[,c("Date","Time","PM2_5","DayNight")],groups=DayNight,shuffled=c("PM2_5")))Let’s shuffle the data and see what that means for the distribution

of mean PM2_5 differences between day and night.

### Create random differences by shuffling the data

randomizing_diffs <- do(1000) * diff( mean( PM2_5 ~ shuffle(DayNight),na.rm=T, data = airDF) ) # calculate the mean in PM2_5 when we're shuffling the day/night values around 1000 times

# Clean up our shuffled data

names(randomizing_diffs)[1] <- "DiffMeans" # change the name of the variable

# View first few rows of data

head(randomizing_diffs)Now we can visualize the distribution of simulated differences in mean PM2.5 levels. Where would our observed difference in mean light levels fall?

gf_histogram(~ DiffMeans, fill = ~ (DiffMeans <= obs_diff),

data = randomizing_diffs,

xlab="Difference in mean PM2.5 across day/night under null",

ylab="Count")In the end, how many of the simulated mean differences were larger than the value we observed? Based on this value, if we were using the conventional \(p\)-value (probability value) of 0.05, we would conclude that because this simulated \(p\)-value < 0.05, that we reject the null hypothesis. There is a difference in mean PM2.5 level between day and night.

# What proportion of simulated values were larger than our observed difference?

prop( ~ DiffMeans <= obs_diff, data = randomizing_diffs)2.2 Calculating correlations between numeric variables

Let’s say that instead of comparing PM2.5 across day and night, I want to compare PM2.5 against temperature. PM2.5 and temperature are both numeric variables. There aren’t obvious categories for either variable.

What do these two variables look like? What does the potential relationship between them look like? We can use a scatterplot to find out.

p <- ggplot(airDF, aes(x=Temperature, y=PM2_5))

p <- p + geom_point()

p <- p + labs(x="Temperature (*C)",y="PM2.5 (PM2_5)")

p <- p + theme_bw()

pIf I’m interested in seeing if

lower temperature is associated with lower (or higher) PM2.5 levels.

I can measure that by calculating a correlation coefficient.

### Calculate observed correlation

obs_cor <- cor(PM2_5 ~ Temperature, data=airDF, use="complete.obs") # store observed correlation in obs_cor of PM2_5 and Temperature

obs_cor # print out valueIs this correlation coefficient meaningful? Let’s test that against a null hypothesis. Our null is that there’s no meaningful association. That is, the correlation coefficient is actually 0.

How then do I know that my correlation coefficient is significantly different from 0? We can tackle this question by simulating a ton of correlation coefficient values from our data by shuffling it!

In this case, the shuffling here lets us estimate the variation in the correlation coefficient given our data. So we are curious now if the distribution of simulated values does or does not include 0 (that is, is it clearly \(< 0\) or \(> 0\)?).

### Calculate correlation coefs for shuffled data

randomizing_cor <- do(1000) * cor(PM2_5 ~ Temperature,

data = resample(airDF),

use="complete.obs")

# Shuffle the data 1000 times

# Calculate the correlation coefficient each time

# By correlating PM2_5 to Temperature from the

# data table airDFWhat are the distribution of correlation coefficients that we see when we shuffle our data?

quantiles_cor <- qdata( ~ cor, p = c(0.025, 0.975), data=randomizing_cor) # calculate the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles in our simulated correlation coefficient data (note that 97.5-2.5 = 95!)

quantiles_cor # display the quantilesThe values above give us a 95% confidence interval estimate for our correlation coefficient!

Do we clearly see that our correlation coefficient distribution does or doesn’t include 0?

gf_histogram(~ cor,

data = randomizing_cor,

xlab="Simulated correlation coefficients",

ylab="Count")In this case, our simulated correlation coefficient does not include

in its 95% simulated confidence interval (we actually never see any

values close to 0 here!). We can also see this in the plot. So given

these data, we would also reject the null hypothesis that

there is no association between PM2.5 and temperature.

On the other hand, if we had seen 0 in the interval, then we would conclude that given the data, we cannot reject the null hypothesis. In that case, there is not sufficiently strong data that PM2.5 correlates with temperature in any clear way.