Air quality lab: Week 2

2021-11-30

Week 2 Lab Overview

Objectives

In lab this week, we will perform the following:

- collect data from PL Air sensors along transects;

- revisit and enhance community guidelines to also incorporate field safety;

- develop questions as PL Air groups to explore.

Time permitting, we may also take on the following tasks:

- viewing and interacting with the PL Air data from week 1 in

Rusing RStudio Server.

We are working toward the climate/air quality group report described here.

Designing environmental data collection

One ubiquitous method of field sampling is the transect sampling method. For transect sampling, one typically takes data at specific, equally-spaced locations along a gradient or across (micro)habitats. For one example of transect sampling air pollution, please see this Public Lab write up and/or this Inside Ecology write up. This is also a form of systematic sampling, as you would be taking measurements at locations based on a fixed pattern. For more background on sampling procedures and guidance on one way to think through sampling design, please visit this Environmental Chemical Analysis site. Note that not all of the examples there are relevant (e.g. biodiversity sampling, soil sampling), but the general principles in Sections 2.1, 2.2 (our sample is more akin to a “grab sample”), and 2.4 are pertinent.

Lab steps

Taking data with your PL Air teams

- Note that you can always see who is in your group by navigating to the Roster sub-page on Sakai then going to Group and selecting your group’s name.

- With your groups, you will select an initial location to test out running a transect with your PL Air units.

- I strongly recommend bringing a notebook and having one member of the team act as a timer. The timer (or another member) can also keep track of your distance between points. Questions to consider include: How far apart should your points be? How long should you collect data at each location?

- Here is a list of suggested locations. Quyên and I will circulate among the groups.

- Pomona College Organic Farm / 1st street

- Marston Quad and College Avenue

- Foothill Avenue and College Avenue

- Former gymnasium and active construction site near 6th and Amherst.

- As an initial exercise, we will allocate up to 1 hour collecting data.

- In that time, I would recommend performing replicates of your transects.

- I would recommend taking data at stationary points at different distances for instance to your site of interest. (Consider how the different sites could vary in terms of air quality.)

- The mobile application

Google Earthcan be used to determine your distance to a point of interest.

Enhancing the community guidelines document

Before we revisit the community guidelines document, please read this article in Small Pond Science (content warning: references sexual assault) and this Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America article (please pay special attention to Table 1).

Here are some guiding questions to consider. There are additional questions that we can and should consider as a group! Please share them, and if you are uncomfortable sharing them directly, you are welcome to anonymously pose the question in the Google doc.

- When and where does working in teams or small groups enhance field safety? When might working in teams or small groups be less than ideal for safety?

- What are the signs of physical or emotional distress? How can we support and look out for one another?

- When and where can technology facilitate safety? When and where might technology undermine field safety?

- What are examples of conditions that are unsafe in the field? How can we avoid them? How can we look out for one another with respect to avoiding these conditions or dealing with these conditions constructively?

- One example could be contact with a poisonous plant such as poison oak.

- Another could be a confrontation with another person, which could be driven by larger systemic biases.

- Finally, conditions such as uneven terrain or very open locations with no tree cover could pose issues in this time of year (or in general).

- What are best practices for communicating our comfort or discomfort in the field?

- What are the potential physical, emotional, or other barriers to participating in different forms of field work or field work in different types of locations?

Developing your group project

For this laboratory project, you will have several decisions to make:

- What question do we seek to explore with PL Air data? What variable(s) are we particularly interested in?

- What is an appropriate distance between sampling points?

- What, if any, sources or locations do we seek to sample?

- How long should we remain at each point to collect the data?

- How many replicates should we take of our data? In this context, replicates could mean the combination of distance to a location/source, time duration, and variable measured if these are variables of interest to your group.

This resource from the Royal Geographical Society may provide additional insight into designing your transects.

A note on replicating data

How might you replicate data collection to try and account for uncertainty in individual estimates? Generally there are two broad ways to achieve this: spatial replication and temporal replication. In working with your groups, please discuss the salient variables that could affect your question (e.g. distance to a road or a construction site for pollutants, tree cover for a heat island effect, and time of day). You can then develop a plan to collect data.

Additional air pollution information

Note that the PL Air units report AQI, PM 2.5, PM 10, and O3 data. You can toggle back to the previous week’s Air Quality page to see Myriad Sensors’ (PL Air company) description of how these values are estimated. However, if, for instance, you are interested in the raw values of PM 2.5 that are reported, you may wonder how these values are converted to and from AQI scores. You can navigate to this AirNow calculator to see how your data maps to AQI. If you would like to see the interpretation of AQI values, please check out this AirNow explainer site. Note - researchers are still developing ways to take the much more instantaneous data we observe on the PL Air and other sensors to “instant exposure” AQI scales. For now though we can use the 24-hour averages for PM and submit the observed data to see that mapping play out (between \(\mu g/m^3\) to AQI scores).

Analyzing PocketLab Air data

This component of the laboratory may be pushed to a later date if time does not permit in lab. In general, one straightforward way to interact with the PL Air .CSV data is to use Google Sheets. The first thing we need to do though is authorize access to our Google accounts in RStudio Server.

Interacting with PocketLab Air data as a Google sheet

Android data

library(googlesheets4)

library(dplyr)

### Here we are pulling in the Google Sheets data from team Paprika

airDF <- googlesheets4::read_sheet("https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/14l_xiqddGl2IFpOPsjfCSSLaHLVeunBhsToimXFuPrA/edit?usp=sharing") # here, we're saying - go to this URL, pull in the Googlesheet, then store it in an object called airDF

### We can see what our data looks like by calling airDF in the console

airDF # yay!

### If we wanted to see what the average PM value was across the trial, we could, for instance, run

mean(airDF$`Particulate Matter-PM2.5 (ug/m³)`)

### We can also see more information about the variable - min, max, and some quartiles.

summary(airDF$`Particulate Matter-PM2.5 (ug/m³)`)

### We can repeat this for the more smoothed-out values of the 10-minute averaged PM 2.5 data

mean(airDF$`Particulate Matter-10 Min. Avg. PM2.5 (ug/m³)`)

summary(airDF$`Particulate Matter-10 Min. Avg. PM2.5 (ug/m³)`)iOS data

One issue with the iOS data is that the mobile application splinches the spreadsheet data. Typically, we would expect to see all of the data in a tidy set of columns, where each row is a particular time point. However, the iOS PocketLab application basically creates a new mini-spreadsheet for each sensor.

Below are the URLs for all of the iOS groups.

- Fresno: “https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/15l8zplAYiLu6kmqPqo0kExe5Ww3RPeSTMlkfv2XoMDc/edit?usp=sharing”

- Aji: “https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1Q9sm9IokCP0lba-ZcBGXG2YkkSOyhRSw-4ijbs1HU-s/edit?usp=sharing”

- Shishito: “https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/17KYbZqLEirxh2cAr6dOlIBJhKo5LWPuvq3dgDPZ-NHA/edit?usp=sharing”

- Bird’s Eye: “https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1QX5ESRLnq3hjeWAPinquTvK9RELK0cMvIEAjBxhG_6Q/edit?usp=sharing”

You can copy and paste this code to run it in the console in RStudio Server to clean up your own data. Note: these steps are only necessary if you have data that was collected using an iPhone.

library(googlesheets4)

library(dplyr)

### Provide a URL

# This URL is for Team Scorpion

gs_url <- "https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1gn6A3uht6e9iQ3qCmqGUTFRhP6YZLdejt5yYjhzeQks/edit?usp=sharing"

### Here, we are pulling in Google Sheets data from team Scorpion

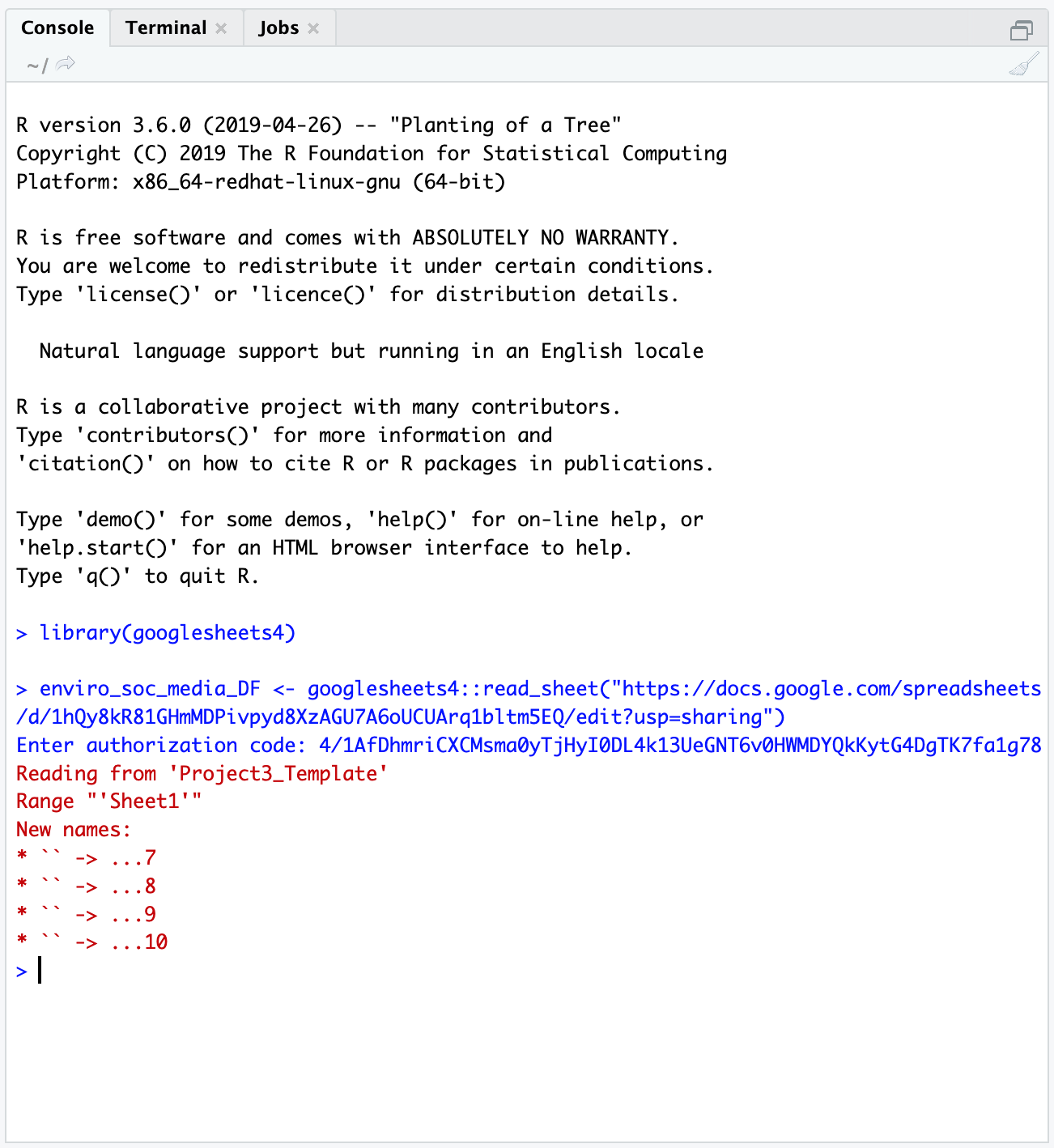

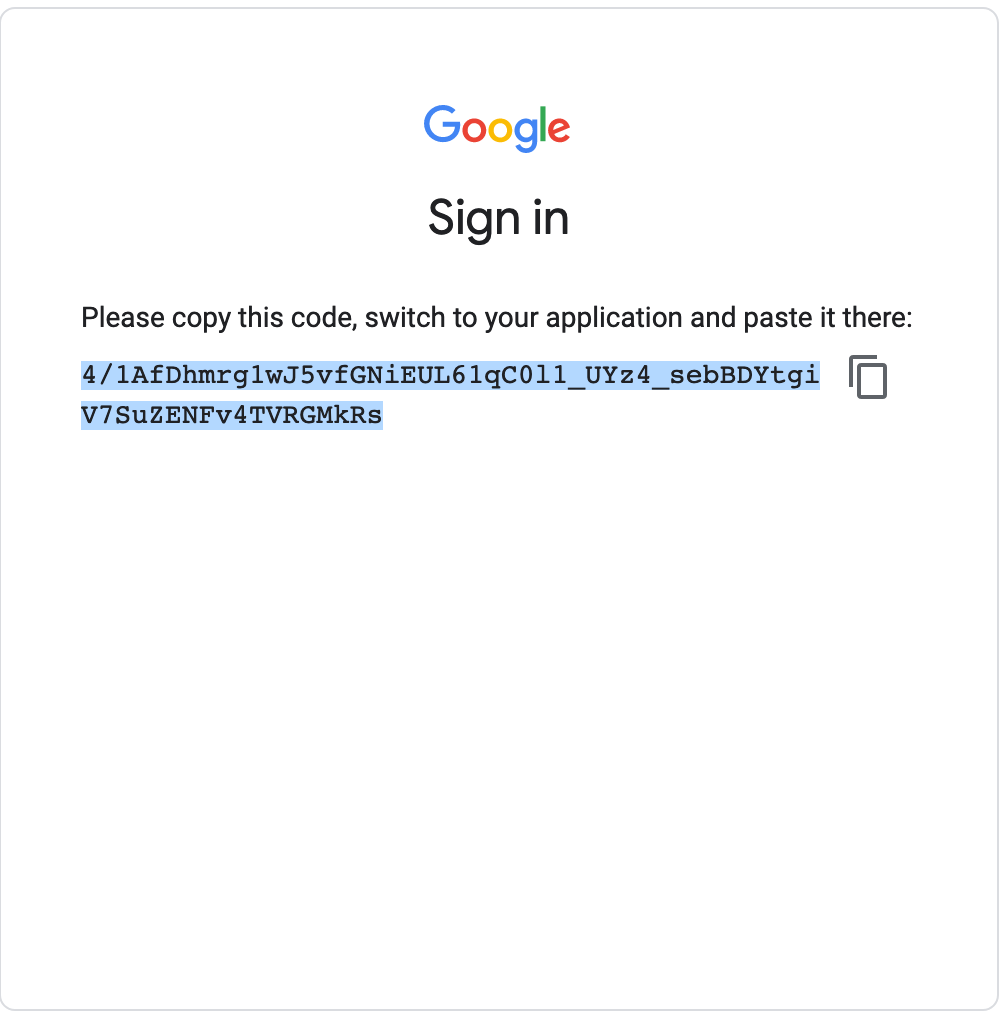

airDF <- googlesheets4::read_sheet(gs_url,sheet=1) # we are storing the default file read in as airDFWhen you run the lines above (airDF <- ...) you may see this message from googlesheets4:

The googlesheets4 package is requesting access to your Google account. Select a pre-authorised account or enter '0' to obtain a new token. Press Esc/Ctrl + C to abort.

1: yourEmail@gmail.com

Selection: Type 1 next to Selection: and hit enter, then you can proceed.

### Reading in the same data, but in a more structured way

airDF_struct <- googlesheets4::read_sheet(gs_url,sheet=1,col_types="nntnnnnnnnn") # here I am reading in the same file but specifying the data types in the column (number or time-stamp) and storing it in a different object called airDF_struct

### What happens when we type airDF in the console?

airDF # cool! We see a subset of our data displayed

### We are going to pull in several helper functions

### using the command "source"

### FMI: ?source

source("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/EA30POM/Fall2021/main/helpers/CleanPLiOS.R") # you only need to run this code once per session

### Using a helper function to clean up our iOS Air Data

airCleanDF <- cleanup_air_function(airDF,airDF_struct)

### Viewing our clean data

airCleanDF %>%

head() %>% # view first 6 rows

View() # pop up an Excel-like data viewer.

### Saving the clean data:

### Option 1: Add a new sheet to your Google Sheet with the clean data

googlesheets4::write_sheet(airCleanDF, ss=gs_url, sheet="Clean") # this will create a new sheet called "Clean" for the clean data.

# Then you can go into the Google Sheet to download the CSV file and upload that to the PL Notebook site.

### Option 2: Saving it as a CSV file

### You will then need to download the file to your own

### computer use it.

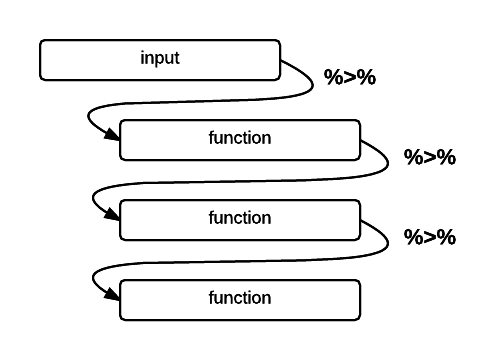

readr::write_csv(airCleanDF,file="~/PLAirDataClean.csv")In the last segment of the code above, you might notice something interesting looking: this %>% pipe operator. The pipe operator %>% lets you daisy chain commands together into a sequence. It is a handy way to make a complex operation with intermediate steps more transparent. The visualization below describes what pipes do in R in linking up functions:

Schematic of the pipe %>% operator in R (Altaf Ali)

Now that we finally have clean data (yay!) we can calculate the same types of summary statistics.

### Calculating the mean and summary statistics for PM data

mean(airCleanDF$`PM2.5 (µg/m³)`)

summary(airCleanDF$`PM2.5 (µg/m³)`) # note that the variable names are a bit different from the Android ones

### We can also repeat this for the smoother averaged values

mean(airCleanDF$`Mean PM2.5 (µg/m³)`)

summary(airCleanDF$`Mean PM2.5 (µg/m³)`)Class activity - evaluating the signs of climate change

We are going to encounter some methods for interacting with, visualizing, and analyzing earth sciences data in this activity. At each table, one student will pick one of the datasets and run the code associated with that dataset. What do you see? Based on the course materials, how does this constitute evidence for global climate change?

First, we will all load these packages - make sure you run this code irrespective of whichever variable you select.

library(dplyr)

library(openxlsx)

library(ggplot2)

sheet_url <- "https://github.com/EA30POM/Fall2021/raw/main/data/ClimateChangeSigns.xlsx" # location of the Excel spreadsheet

keelingCO2 <- openxlsx::read.xlsx(sheet_url,sheet="Keeling") # everyone needs to download the Keeling CO2 data because we will be combining that with the other variables too.Variable 1: Global \(CO_2\) concentration in the atmosphere

The data source for this variable is NASA’s Global Climate Change Vital Signs of the Planet Program.

p <- ggplot(keelingCO2, aes(x=year,y=meanCO2ppm))

p <- p + geom_point()

p <- p + geom_line()

p <- p + labs(x="Year",y="CO2 (ppm)")

p <- p + theme_classic()

p

CO2mod <- lm(meanCO2ppm~year, data=keelingCO2) # we are running a "linear regression" statistical model. You can think of this like finding the line that fits our data the best.

summary(CO2mod) # what do you see in the Coefficients: table for year?Variable 2: Arctic sea ice minimum spatial extent

The data source is here.

seaIce <- openxlsx::read.xlsx(sheet_url,"SeaIce")

seaIceCO2 <- left_join(seaIce, keelingCO2, by=c("year"="year")) # we are joining up the sea ice extent data with global CO2 level data, matching on each year

p <- ggplot(seaIceCO2, aes(x=meanCO2ppm, y=extent))

p <- p + geom_point()

p <- p + geom_line()

p <- p + labs(x="CO2 (ppm)",y="Minimum sea ice extent (million km2)")

p <- p + theme_classic()

p # what do we see?

seaIceMod <- lm(extent ~ meanCO2ppm, data=seaIceCO2) # we are running a "linear regression" statistical model. You can think of this like finding the line that fits our data the best.

summary(seaIceMod) # what do you see in the Coefficients: table for mean CO2 (ppm)? Variable 3: Global surface temperature (land and ocean)

The data source is here.

globTemp <- openxlsx::read.xlsx(sheet_url,"GlobTemp")

globTempCO2 <- left_join(globTemp, keelingCO2, by=c("Year"="year")) # we are joining up global temperature data with global CO2 level data, matching on each year

p <- ggplot(globTempCO2, aes(x=meanCO2ppm, y=TempObs))

p <- p + geom_point()

p <- p + geom_line()

p <- p + labs(x="CO2 (ppm)",y="Global temperature anomaly (*C)")

p <- p + theme_classic()

p # what do we see?

tempMod <- lm(TempObs ~ meanCO2ppm, data=globTempCO2) # we are running a "linear regression" statistical model. You can think of this like finding the line that fits our data the best.

summary(tempMod) # what do you see in the Coefficients: table for mean CO2 (ppm)? Variable 4: Heat content of the oceans

The original data source is here but the data I used came from the EPA. The ocean’s heat content is expressed in zettajoules or \(10^{22}\) joules. In contrast, total global energy consumption is around 580 million terajoules, or 5.8 zettajoules.

oceanHeat <- openxlsx::read.xlsx(sheet_url,"OceanHeat")

oceanHeatCO2 <- left_join(oceanHeat, keelingCO2, by=c("Year"="year")) # we are joining up global ocean heat content data with global CO2 level data, matching on each year

p <- ggplot(oceanHeatCO2, aes(x=meanCO2ppm, y=NOAASea))

p <- p + geom_point()

p <- p + geom_line()

p <- p + labs(x="CO2 (ppm)",y="Ocean heat content (ZJ)")

p <- p + theme_classic()

p # what do we see?

oceanMod <- lm(NOAASea ~ meanCO2ppm, data=oceanHeatCO2) # we are running a "linear regression" statistical model. You can think of this like finding the line that fits our data the best.

summary(oceanMod) # what do you see in the Coefficients: table for mean CO2 (ppm)? Taking the activity further

Time permitting, consider the following:

- for the

lmcoefficient outputs, what do those numbers represent? What do they tell us about the impact on some response variable for changes in \(CO_2\)?- what is the unit of change in \(CO_2\) for the coefficients?

- how much would your variable change if \(CO_2\) went up by 10 ppm?

- can we reasonably extrapolate those estimated valus into the future?

- how would you modify the code above to re-run the analyses with

Yearas the explanatory/predictive/x-axis variable?

6. Paste the authorization code into the blank space next to

6. Paste the authorization code into the blank space next to